111-2期末全院集合 郭朝順院長勉勵話語

2023/ 05 /24

諸位來到學院過團體生活,團體生活中難免有許多不如意,例如:與寮友生活作息相違,行堂典座組員常常遲到、未到或者拖累工作等等。前者我們除了彼此體諒,也應該要協商、溝通,設法取得共識;對於後者,則應提醒、規勸,讓每個人將大眾的事務放在心上,不要將服務大眾之事,作成妨礙大眾之事。

All of you at the college, in the course of experiencing communal living, have likely encountered difficulties, such as (i) roommates with conflicting living habits and (ii) cooking-serving rotation team members being late, absent, problematic, etc. For the former (i) kind of conflict, in addition to mutual empathic understanding, we should do our best to negotiate, communicate, and reach a consensus; for the latter (ii) kind of conflict, it is necessary to remind and encourage everyone to sincerely respect communal duties and to avoid degrading otherwise laudable service to the community into subpar disservice.

對不如意之事,人都難免會生起怨懟,乃至起了瞋心。就心理學的講法,人不該壓抑情緒,才不會產生過度的壓抑,可是佛教卻教我們修忍辱行,這二者之間會不會產生對立?

People inevitably develop resentment and even anger toward disagreeable situations. According to psychology, one should not repress emotions in order to avoid dysregulation, but Buddhism teaches us to practice forbearance. Are these two notions in conflict?

怨瞋有個基本特性,它總是在他人傷害或者侵犯我時出現。即便如路上的狗兒,只要覺得自己的地盤受到威脅,便會吠叫示威、露齒威脅,這便是捍衛自己地盤的本能。所以,如果「我」的界限很大,那你便會不時感到旁人時時在威脅、侵犯,也就時時會起瞋心;如果「我」的界限小一點,你便較不易感到被冒犯。到了「無我」時,便是完全不會因自覺被冒犯而生起瞋心。

Resentment, or anger, has a fundamental characteristic: it arises when we perceive others to harm 'me.' Even street dogs that sense encroachment of their territory will bark and bare their teeth as an instinctive, primal defense response. Similarly, if the territory of your 'self' is very large, then you will constantly feel threatened or impinged and get angry often; if the territory of your 'self' is smaller, you are less likely to get offended. When there is 'no-self', there is no longer any possibility of anger arising from perceived intrusions.

可是還有另一種瞋心會出現的狀況:雖然未必受到傷害或者威脅,但若有人可以歸咎的話,自己便可以理直氣壯地宣稱自己沒有錯。這依然是一種自我保護的自然反應。由此來看,瞋心的出現始終和自我防衛之本能反應息息相關。

But there is another situation in which anger may arise: shifting blame to someone else (despite the absence of any actual harm or threat) allows us to self-righteously proclaim our own inculpability. Such scapegoating is yet another instinctual ego-preservation response. From this perspective, the emergence of anger is always closely related to ego-defensive instinct.

是以,心理學所謂的不要壓抑情緒,便是不要否認自己有這樣的本能,面對它才有可能超越它,更何況,旁人犯過卻由我承擔,確實是不公平的。所以,我認為忍辱行不是要人否定情緒,也不是要人忍受不公,而是要人認知情緒並且超越情緒的本能反應,超越自我防衛的心態,以堅毅之力承擔在不善因緣狀況下所產生的壓力,同時處理好眼前的因緣。

As such, when psychology says not to suppress emotions, it is not to deny that we all have such instinct. Only by acknowledging our ego can we begin to transcend it. To take responsibility for others' faults is indeed unfair. So, I believe that the practice of forbearance does not require people to deny their emotions or endure senseless injustice, but rather to recognize their emotions and to transcend instinctive reactions, transcend our habitual self-defensive mentalities, and bear the stress of adverse situations with grit while skillfully handling the task at hand.

當他人犯錯殃及我時,我可以對他表示對此行為的不認可,但不要僅停留在為自己打抱不平,或只是為自己了出一口氣的層次,而是為了引導向善,為了利益大眾。這時候,忍辱行除了堅毅的承擔外,同時也就包含了,敢不敢將責備求善的規勸,用不帶瞋心且是確能引導向善的方式,宣之於口的智慧與勇氣之修練。

When others' mistakes implicate me, I can express my disapproval of their actions to them, but I don't have to stay simply at the level of vindicating myself from undue grievance or venting my frustration: I can have the greater motivation of wanting to positively influence others to bring out their innate potentials for virtue so as to ultimately benefit the greater community. At this point, the practice of forbearance includes not only tenacity and fortitude, but also the courage to do what is not easy but is right: to correct others so they can improve. To frankly communicate what is necessary without anger is a practice of wisdom and courage that can genuinely benefit others.

忍辱行不是要讓自己成了受氣包,令不正義不公平的事情恣意發生,忍辱行是為了令人有堅毅承擔的力量,以及超越自衛本能的氣度,並有著頂住壓力的勇氣,以及解決問題的慈悲與智慧。因此,忍辱行中的無我,便是徹底超越狹隘自我且勸導眾生行善的修行,正如《法華經》常不輕菩薩之甘願承擔眾生的詈罵永不退轉一般。

The practice of forbearance is not about making ourselves into submissive enablers, pushovers, or martyrs and allowing injustice and wrongdoing to proliferate. The practice of forbearance is about inspiring ourselves and others to be strong and enduring, transcending our limited ego-preservation instincts, and developing the courage to withstand pressures as well as the compassion and wisdom to solve problems. Therefore, the practice of egolessness, which underlies the practice of forbearance, completely transcends ego's limitations and exhorts everyone towards their innate potentials for virtue, just as in the Lotus Sūtra, the Bodhisatva Sadāparibhūta (Never Disparaging) never regressed in his willingness to honor sentient beings despite their constant disrespect of him.

佛經中忍辱仙人的故事十分有名,不過,正如我以往說過,佛經不能只從字面上讀,大家若依上述的說法來讀,也許會讀出不一樣的內涵。祝大家吉祥如意。

The story of Kṣāntirṣi (who endured senseless mutilation of his body) in the Mahāyānasūtras is quite famous, but as I have said before, the Buddhist sūtras cannot be read only literally. If you read with the above-stated points in mind, you might understand another level of meaning. I wish you all the best!

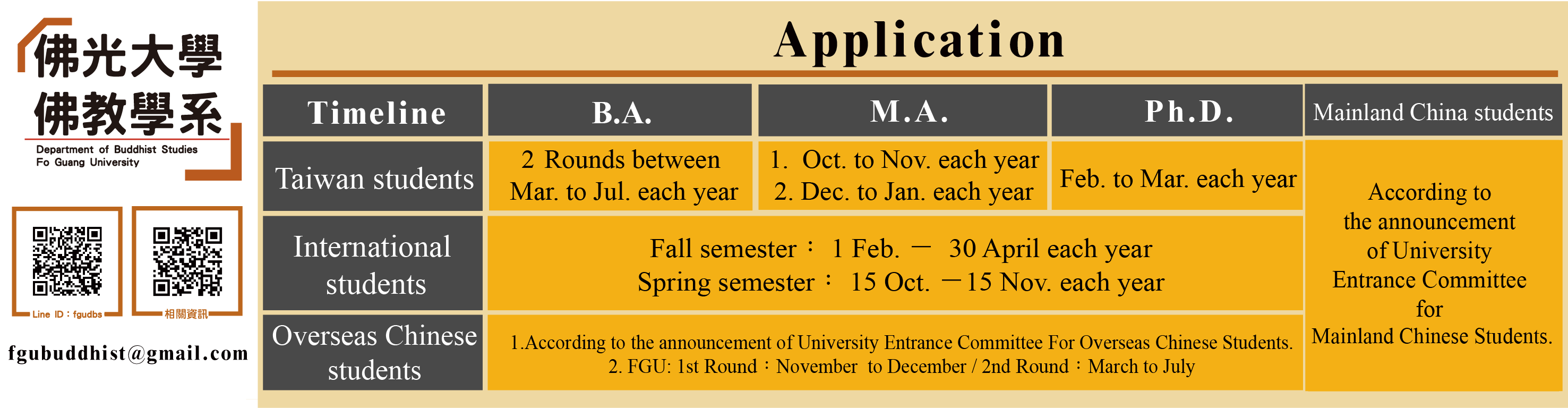

College and Department of Buddhist Studies, FGU

College and Department of Buddhist Studies, FGU